Practice Yoga and Live Life to its full potential : Part 2

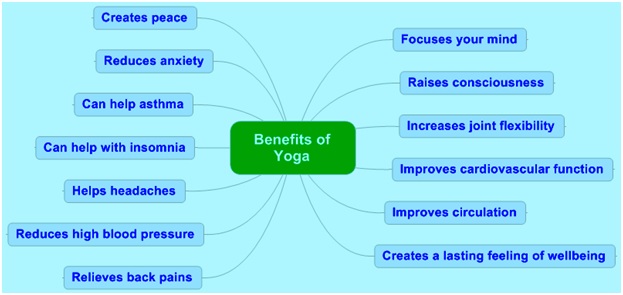

21. Improve coordination : No matter one’s age is, yoga nurtures better connections between the muscular and skeletal systems.

22. Improve lung capacity : The disciplined breathing exercises that yoga entails can increase a practitioner’s lung capacity, which improves their overall physical performance.

23. Complement occupational and physical therapy: Practicing yoga is an excellent way to build physical therapy regimen.

24. Prevent heart disease: Practicing yoga regularly tones the muscle, particularly cardiac muscles and helps prevent heart diseases.

25. Soothe insomnia.: Insomnia and other sleep disorders can be cured by practicing several yoga postures.

26. Relieve Multiple Sclerosis: Many yoga positions can be tailored to specifically meet the needs of practitioners suffering from Multiple Sclerosis, helping them stay healthy and alleviate some of the suffering.

27. Alleviate menstrual cramps: The practice of yoga appeals greatly to women who experience severe cramps during their periods, as it strengthens abdominal muscles and fortifies them against the pain.

28. Massage the internal organ : Thai yoga provides organ tissues all over the body with a revitalizing massage to keep them stimulated and operating smoothly.

29. Lubricate joints : Among the many other skeletal and muscular benefits that pop up during regular yoga sessions, adherents can also enjoy well-lubricated joints, tendons and ligaments as well. This leads to enhanced flexibility and injury prevention.

30. Balance hormones : During menopause, women may want to get into yoga as a means of strengthening their endocrine system and encouraging hormone production through lessened stress.

31. Detoxifying effect: Encourage the body to release any harmful chemical buildups or cellular waste by cycling through yoga moves designed specifically for detoxification.

32. Encourage meditation: Some yoga practitioners enjoy the spiritual element of the discipline, appreciating how the associated deep breathing exercises place them in a viable meditative state.

33. Lower the triglyceride count: Use yoga techniques to dissolve the triglycerides that float about in the blood stream and pose a serious threat to cardiovascular health.

34. Burn off post-baby fat. : Following a pregnancy, one can slough off a bit of the accumulated baby weight using postnatal yoga – the lesser-known counterpart to prenatal yoga.

35. Improve self-confidence: Engaging in regular yoga sessions has the potential to facilitate self-confidence and improve upon poor body image and other psychological issues.

36. Kick off migraines: Migraine sufferers would do well to consider yoga as a possible conduit for ridding themselves of their debilitating pains.

37. Anger management: Yoga’s calming, stress-relieving properties carry with them the additional benefit of serving as an excellent means of reining in the psychological and physiological damages associated with too much anger.

38. Improved respiration : All disciplines that fit underneath the broad heading of “yoga” require deep breathing exercises that encourage stronger, healthier lungs.

39. Improved depth perception: Heavily spatial exercises such as yoga require participants to make note of the people and objects in their vicinity, helping them build stronger depth perception along the way.

40. Relieve constipation: When the bowels back up and the thought of downing glass after glass of prune juice seems unappealing, try some yoga positions that explicitly help users unbind.

Author: HealthyLife | Posted on: June 17, 2015

« Practice Yoga and Live Life to its full potential : Part 1 Practice Yoga and Live Life to its full potential : Part 4 »